The close-to-home reason this USC brain scientist is trying to figure out Alzheimer’s

Arthur Toga saw the disease ravage his family, so he’s worked to transform what scientists know and think about the memory-erasing illness that affects 1 in 3 seniors

Alzheimer’s robbed Arthur Toga of his grandmother. Then his aunt. By the time it struck his mother, Toga knew the horrors that the memory-erasing disease would bring. He described what obstacles lay ahead to his two younger brothers.

“My family and I needed to prepare ourselves. The degree of loss that you feel when you see somebody’s personality and their whole being erased …” said Toga, his words trailing off.

“I knew what stages were coming, but you’re never prepared for what this disease not only does to the person, but also what it does to you,” he said. “They go inside themselves. They stop communicating. They stop interacting with the outside world whether it’s to eat food or anything.

“They often, like in my mother’s case, literally stop living. And you don’t get to say goodbye because their mind is no longer present.”

Being a witness to Alzheimer’s disease kill the women in his life pushed Toga to look for ways to prevent others from going through what he and his family suffered. After Toga’s mother passed away, he was a Provost Professor of Ophthalmology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and one of the world’s leading researchers working to solve the Alzheimer’s problem, which affects 1 in 3 seniors and is among the most intractable problems in human health.

Toga is director of the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute and leads 35 faculty and postdoctoral scholars — researchers in neuroscience, physics, engineering, and math — who have contributed to neuroscience in significant ways. In all, USC has more than 70 researchers across multiple disciples devoted to neurodegenerative research: medicine, gerontology, pharmacy, humanities, engineering, social work and public policy.

Mark Stevens chats with Toga at the 2016 opening of the USC Stevens Hall for Neuroimaging. (Photo/Steve Cohn)

The team digitizes and maps mice and human brains to help locate ways to fix or preempt neurodegeneration. The institute hosts the largest collection of brain data in the world, housing more than 4,800 terabytes of information — the equivalent of over 50 million movies in 4K — from every continent except Antarctica. It receives images taken from National Institutes of Health-funded stroke clinical trials, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative and dozens of other multi-site projects. Patterns in this collection of brain scans could lead to ways to better diagnose and treat neurodegenerative conditions.

“I don’t think there are any other examples of data collections of this magnitude with this level of success,” Toga said. “Our techniques are revolutionary because they allow us to, in a matter of minutes, do something that, even if you could conceive it before, would have taken years! Now we can do it in minutes. This is going to accelerate the pace of discovery beyond our wildest imaginations.”

Brain science transformed

Toga, 64, was once a pre-med student but switched gears and graduated with a degree in psychology.

“I became fascinated with how the brain might be organized and where its weaknesses may be,” he said. “I like the notion of putting these different puzzle pieces together, thinking about how we can understand the human condition. Let’s face it, your brain is the human condition because all of your experiences and emotions live there.”

Early in his career, Toga realized that simply understanding the brain would not be enough to solve a wicked problem. So, he went back to school to learn how to manipulate and interpret large amounts of brain images and data. Though he didn’t finish his master’s in computer science, this time would prove invaluable as computers became capable of storing and crunching prodigious amounts of image data.

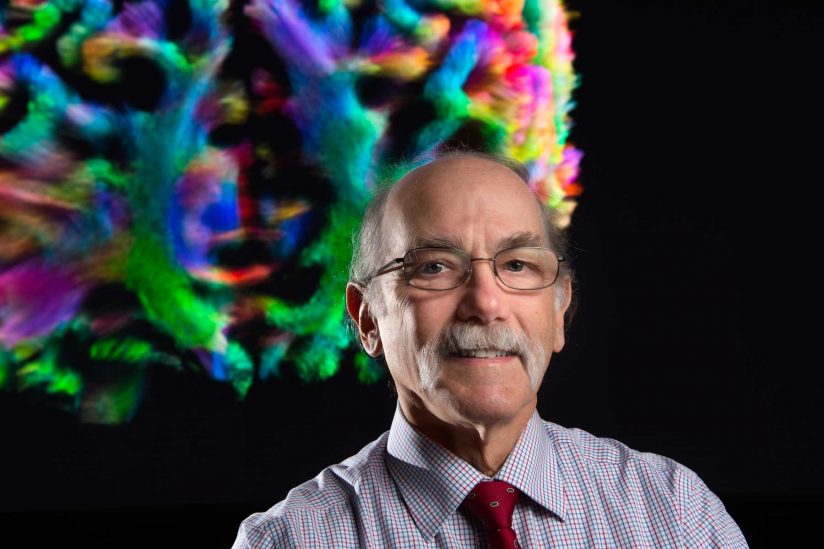

Toga is one of the founders of a big-data approach to understanding the brain and its diseases. Using high-powered computers and secure servers, Toga’s group analyzes vast amounts of data to find trends peculiar to specific populations and produces brain images with all the colors of the rainbow. Ironically, he can see only some of them because he is colorblind.

“When I first started, Alzheimer’s was a disease where people knew about tissue lost. Most of the time, it was considered to be diagnosable only after death.”

Arthur Toga

“My research and that of many others revealed that your brain’s circuitry begins to jam decades prior to the cognitive issues that the patient experiences. The brain’s cognitive reserve is able to compensate until a breaking point,” said Toga.

A colossal problem

Sitting at his giant, frosted-glass desk, Toga looked small as he pondered the colossal problem that is Alzheimer’s disease. He looked at a wall clock with its internal workings in full display, indicative of how he examines tens of thousands of brain scans to figure out how brain size and circuits change over time.

The Global Alzheimer’s Association Interactive Network, one of several large projects that Toga leads, enable scientists to toggle through data on more than 366,000 patients to locate subgroups of people for further study, such as women or people with early onset Alzheimer’s.

Toga is also the director of the Laboratory of Neuro Imaging, a leader in the development of algorithms and approaches for the mapping of brain structure and function. LONI hosts more than 60 national and international brain imaging collaborations.

The tools and maps Toga and his researchers create are changing how people understand healthy and diseased brains. Scientists and doctors cannot fix a problem they can’t locate. Telling a plumber to fix a leaky faucet by coming to California is not as effective as giving the technician a home address. Toga and his collaborators are drawing a road map to the problem areas of diseased brains.

One of the trends researchers at the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute discovered is that the hippocampus — the brain’s memory center — is smaller than average in depressed people. The longer people suffer from the illness, the more their brain will differ from a typical brain, meaning the ability to treat depression early could slow the progression of brain tissue deterioration.

Toga is working with Berislav Zlokovic, director of the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute at the Keck School of Medicine, to investigate how blood flow and blood vessel integrity in the brain affect the mind’s wiring in people at-risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Zlokovic is internationally recognized as a leader in how lesions in the brain’s vascular system could fast-track dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“Art Toga’s studies of connections between different brain regions associated with memory and brain structure will provide new and important biomarkers for early changes in cognition,” Zlokovic said. “This work could identify potential therapeutic targets that precede the buildup of amyloid-beta and tau proteins — the standard markers of Alzheimer’s disease progression.”

Neurodegenerative diseases cannot be treated as a monolith, said Rohit Varma, dean of the Keck School of Medicine. Some people are more at risk because of their genetic makeup. Others are more receptive to certain treatments or interventions.

“Our team of physicians and scientists are facilitating a deeper understanding of neurodegenerative diseases,” Varma said. “With Alzheimer’s disease, for example, we have more than a dozen clinical trials and many basic researchers examining the illness from diverse angles such as the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier and how prolonged exposure to tiny air pollution particles can speed up dementia.

“Over the course of his career, Dr. Art Toga has made incredible strides toward understanding the causes behind Alzheimer’s disease. Toga’s body of research has been transformational and has guided the way other physician-scientists around the world study the disease. We are truly privileged to have Dr. Toga and his team leading the charge in this disease area — which is so timely given our aging boomer population and the enormous cost, both economic and personal, of this devastating disease.”

BY Zen Vuong