Death of the Middleman? USC Researchers Imagine a Cheaper, Fairer Marketplace For Digital Goods

Beyond improving e-commerce, USC Viterbi’s Bhaskar Krishnamachari sees a blockchain-driven future where cars, homes and appliances can buy and sell digital information.

Beyond improving e-commerce, USC Viterbi’s Bhaskar Krishnamachari sees a blockchain-driven future where cars, homes and appliances can buy and sell digital information. E-commerce is sizzling. Last year, consumers spent more than $517 billion online with US merchants, up 15 percent from the year before, according to Internet Retailer.

However, independent musicians, self-published authors and others have sometimes found it difficult to participate in the e-commerce revolution. That’s because they typically must set up an account with a third party, say a credit card company, to protect against fraud while simultaneously increasing the comfort level of potential buyers. Those credit card accounts, though, cost money. That can result in lower profits for artists and other online sellers and higher prices for buyers.

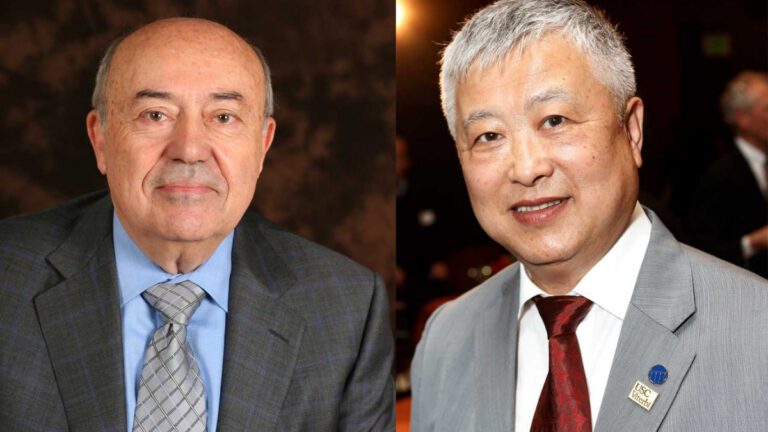

Bhaskar Krishnamachari, a professor at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, and Aditya Asgaonkar – a recent undergraduate computer science alum at BITS Pilani, India who visited and worked with Krishnamachari at USC Viterbi over several months in 2018 – believe they have found a way to make the buying and selling of digital goods less costly, more efficient, and less vulnerable to fraud. Their proposed solution involves blockchain, “smart contracts,” and game theory.

“Our scheme offers potentially a big improvement over the state-of-the-art in electronic commerce because it allows buyers and sellers to interact directly with each other without the need for third-party mediators of any kind,” said Krishnamachari, a Ming Hsieh Faculty Fellow in Electrical and Computer Engineering and director of the Viterbi Center for Cyber-Physical Systems and the Internet of Things.

“It uses a dual-deposit method, escrowing a safety deposit from both buyer and seller that is returned to them only when they behave honestly. And the verification of who is at fault and who is honest is done automatically by the smart contract,” added Krishnamachari.

On May 15, 2019, Asgaonkar presented the researchers’ joint paper titled, “Solving the Buyer and Seller’s Dilemma: A Dual-Dual-Deposit Escrow Smart Contract for Provably Cheat-Proof Delivery and Payment for a Digital Good without a Trusted Mediator,” at the IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency in Seoul, South Korea.

Asgaonkar and Krishnamachari have created an algorithm that runs on a programmable blockchain as a “smart contract.” Blockchains allow multiple stakeholders to transact money or data virtually over linked peer-to-peer computer networks.

Here’s how it might work.

An author wants to sell her digital masterwork, “The Great American Novel.” However, she hopes to avoid going through Amazon or some other company that takes a commission.

Instead, she uses Asgaonkar’s and Krishnamachari’s blockchain-based solution and lists the book’s price at $20. An interested buyer contacts her. To ensure an honest deal, both the buyer and seller agree to pony up a $10 deposit through Ethereum or some other programmable blockchain platform.

The author then sends the digital book to the buyer, who could only access it by making a verifiable payment for the correct amount. If the transaction satisfies everybody, then both parties receive their deposits back.

But what if someone tries to cheat? What happens, for instance, if the seller intentionally sends the wrong e-book? What recourse does the aggrieved party have?

This is where the so-called smart contract kicks in.

The contract stores a good’s digital hash code, or “digital fingerprint,” in Krishnamachari’s words. The buyer has access to that code before making a purchase. If they receive an item with a different hash code, however, they can dispute the transaction. In this instance, the seller would forfeit their deposit after the algorithm determined that they had attempted to cheat the buyer.

Now, consider a different scenario in which the buyer tries to cheat by falsely claiming they received the wrong item. If the digital fingerprint, shows otherwise, the unscrupulous buyer would lose their deposit.

Asgaonkar and Krishnamachari call their system “cheat proof.” Their paper uses game theory to prove mathematically that, in their proposed protocol, the best option for buyers and sellers is to behave honestly, lest they lose their deposits or access to desired goods.

“Our solution, a crypto-economic system, disincentivizes malicious behavior from either party,” said Asgaonkar, now a researcher at the Ethereum Foundation.

Added Clifford Neuman, a computer scientist at USC Viterbi’s Information Sciences Institute: “The significance of this work is that it changes the structure of incentives for correct behavior in online transactions so that the optimal benefit to both parties occurs when they transact fairly.”

At present, Asgaonkar’s and Krishnamachari’s system works only with digital goods because physical products can’t have a cryptographic hash associated with them. However, physical goods stored in a safe-box that can be opened with a digital password could be potentially transacted using their system.

The researchers’ blockchain-based system, under-girded by algorithms and smart contracts, solves what’s known as the “Buyer and Seller’s Dilemma,” all without the need for credit-card companies or legal adjudications, Krishnamachari said.

“The dilemma is that with a traditional online transaction, either the buyer or seller will have to go first, either trusting that the buyer will pay honestly after delivery or that the seller will deliver honestly after payment. But either party has the incentive and ability to cheat the other if no other dispute resolution mechanism or trust third party is involved,” Krishnamachari said.

“By providing for the dual-deposit escrow and an automated verification process as a piece of software running on a blockchain,” he added, “we are able to guarantee that neither party will cheat the other.”

A Future of Microtransactions

What most excites Krishnamachari about this new protocol is its ability to facilitate microtransactions, “which I see as the future of digital commerce among individuals and between organizations,” he said.

Made popular in games and mobile apps, microtransactions allow users to pay small amounts of money for virtual goods like a new sword in “World of Warcraft” or unlocking hidden levels in a game.

However, with the advent of the Internet of Things, the potential for these tiny microtransactions is far, far greater.

Such automated arrangements, for instance, could include micropayments to the owner of a sensor-laden car digitally providing another driver with traffic data or air quality information. These and other microtransactions, Krishnamachari said, will multiply with the increased interconnection, via the Internet, of data-exchanging computing devices embedded in everyday objects.

“Creating these data economies is going to require us to lower the friction for transactions down to zero. And that’s what we’re trying to do,” Krishnamachari said. “Millions of transactions could become frictionless, digitized and monetized, and the Internet of Things would be more robust.”