Scared by artificial intelligence? Fear not, tech-savvy USC grad says

Artificial intelligence. For many, those two words evoke visions of robot overlords running amok and terrorizing citizens.

Artificial intelligence.

For many, those two words evoke visions of robot overlords running amok and terrorizing citizens. Others lament the steady automation of factory and manufacturing jobs, with precise machinery taking the place of humans.

But to Eric Deng, the future of robotics and artificial intelligence isn’t scary at all. Instead, he sees smart machines as a force for social good. Imagine interactive androids that keep older adults company while monitoring their health. Or friendly and engaging robots that help children with autism develop social skills.

As an electrical engineering undergrad and Stamps Scholar at USC, Deng helped program and design robots to begin taking on those socially assistive roles. The recent graduate heads to work at Facebook this fall as its first robotics engineer, with visions of ensuring that artificial intelligence remains safe, helpful and accessible.

“I want to make AI and high-tech systems easier to design, create and use, with the goal of giving more people the opportunity to build these powerful systems to help themselves and others,” he said.

Inspired to bring a human touch to artificial intelligence

Growing up in California’s Bay Area, Deng seemed destined for a career in the tech industry. He drew inspiration from watching his parents, both engineers, work on various projects in their Fremont home. In addition to its technical aspects, he enjoyed the aesthetic side of engineering — how art and design can influence how a product is used or perceived. He was also fascinated by how and why people make certain decisions.

Deng found a good outlet for his mechanical talents as captain of his high school robotics team. During summers, he took university courses in behavioral economics to better understand human behavior. But he wasn’t sure he could find a field that would allow him to combine his eclectic interests. By the time he enrolled at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, Deng had resigned himself to focusing solely on engineering.

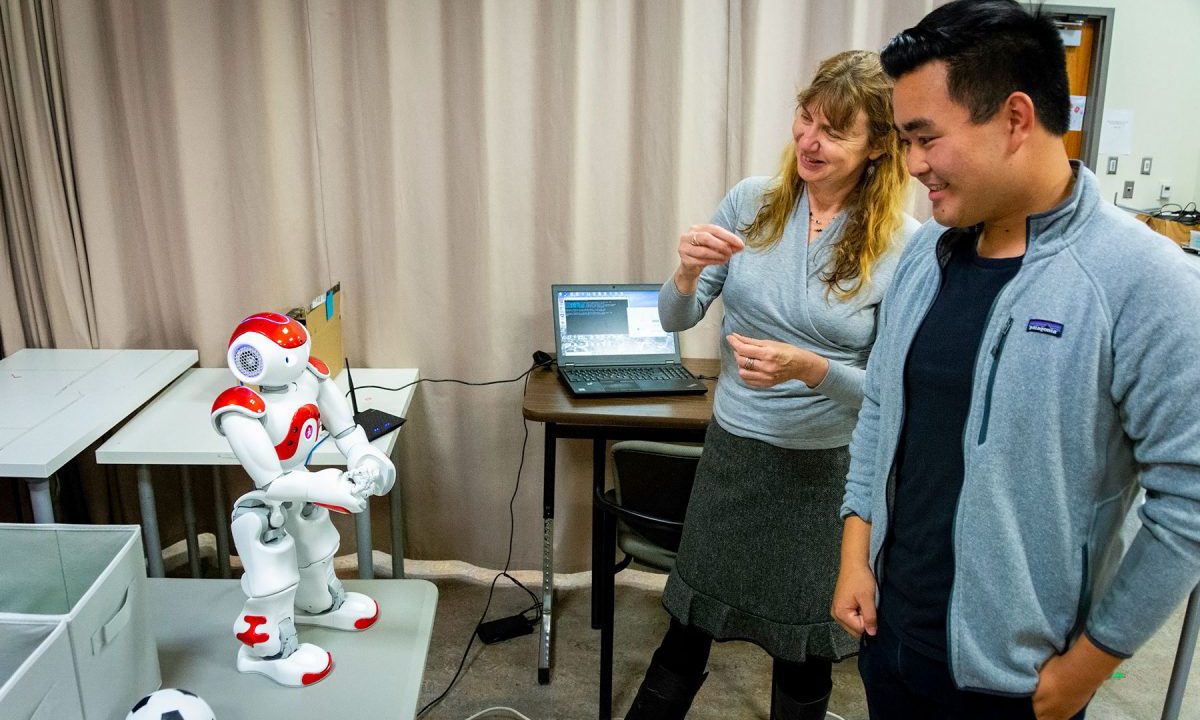

That’s when he stumbled on the Interaction Lab run by Maja Matarić, USC Viterbi’s vice dean for research and the Chan Soon-Shiong Professor of Computer Science, Neuroscience, and Pediatrics. The lab focuses on designing and building robots to help people through social interaction. Its current projects involve developing robot-assisted therapies for survivors of stroke and traumatic brain injury, people with Alzheimer’s disease and children with autism.

The lab’s human-centered approach to artificial intelligence was a great fit for Deng. Rather than just building functional machines to perform a repetitive task, the lab’s researchers have to pay close attention to how robots look, feel and act. Even minor changes in their appearance or behavior can affect how they’re perceived and whether they elicit the desired response.

Some robots, like ones for children, might send the right message if they look cute, Deng said. That’s the wrong look for other robots, though. “If it’s a doctor robot, you don’t want it to be cute,” he said. “You want it to look intelligent and trustworthy and even a little bit more serious.”

Impressed by his early work with her team, Matarić soon took on Deng as a mentee. She acknowledged that many undergrads want to work with her, but they often need guidance and are unsure of their direction. Deng, however, is motivated and self-driven, she said.

“Three years later, he’s basically doing the work of a grad student.”

A complex challenge: making robots seem human

Deng has collaborated with researchers to understand how robots can better follow social norms such as maintaining appropriate personal space or use gestures and nonverbal signals to symbolize various objects.

In another project, he explored how robots can catch and maintain the attention of children with autism. Is it effective to wait patiently or emit soft noises? Are wild and erratic movements counterproductive? The trick is finding the right balance to promote engagement.

“You don’t want to have a mean robot or a rude robot,” Deng said. “The robot could yell and the kid will look up every time, but that quickly deteriorates the rest of the intervention.”

As the hardware lead for the project, he helped design, build and program the robot prototypes, which resemble colorful owls. The research team recently sent a handful of the devices to be tested by kids in their homes, and a short video about the project drew millions of views when shared by Twitter on World Autism Awareness Day.

Deng doesn’t expect these smart machines to replace trained caregivers and therapists anytime soon. Instead, they can fill in the gaps, he said, providing companionship and care when health professionals aren’t available or between regular therapy sessions.

“You aren’t replacing caregivers like nurses,” he said. “You are just allowing them to focus on more complicated work.”

Deng’s achievements in the lab earned him numerous accolades, including the Richardson Endowed Undergraduate Merit Research Award and the Order of Areté. He was named a Viterbi Undergraduate Fellow and Grand Challenges Scholar, in addition to his prestigious Stamps Scholarship, which covered his tuition and provided funding for personal research projects and travel to a major overseas tech conference.

As he wraps up work on a few remaining research papers with fellow Trojans, Deng looks forward to his new position with Facebook, which starts in August. It promises to be a smooth transition — he interned at the social networking giant every summer since coming to USC.

He can’t say much about his new role as its first robotics engineer, partly because the company is just starting to explore new fields.

“The opportunity it presents is pretty exciting,” he said. “It’s so new, you don’t really know what it will turn out to be.”

Killer robots? Highly improbable

As for the future of artificial intelligence, Deng expects to see some automation and replacement of human jobs. But it’s much more likely that the robot revolution will involve assistance rather than automation, he said, with robots encouraging their mortal masters to do better work.

And despite the pop culture cliché of artificial intelligence gone wild, he’s even less concerned about the potential for robots turning into evil monsters intent on destroying society.

“Any technology has potential for harm,” Deng said. “Problems arise when you have homogeneous teams that just think about their specific issue. Then a lot of populations get marginalized.”

As long as we build empathetic, ethical and diverse groups of designers and engineers, he’s convinced humankind has no reason to worry about a robot uprising.